Why is There a Doctor Shortage?

News of a doctor shortage grows as population ages and Medicare funding for residency positions remains capped, leaving hundreds of qualified graduates without training positions each year.

Popular articles

News has grown over the past few years of an impending doctor shortage. The population is growing and aging, while the number of doctors does not keep pace. Some fear that the Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare), by expanding medical coverage to roughly 30 million Americans, will exacerbate the shortage and result in longer wait times to see doctors.

The Association of American Medical Colleges has predicted a shortage of 91,000 physicians by 2020 — 45,000 in primary care, the other 46,000 in specialties and surgery. “Medical schools have done their part by increasing enrollments,” the association claims. The fault, they maintain, lies with the federal government, which supports postgraduate physician education residency program through Medicare funding. “Unfortunately, Congress capped the number of Medicare-supported residency training positions in 1997 [with the Balanced Budget Act] and, unless there are more residency positions, these new M.D.s will not be able to complete their training and practice independently.” Medicare provides $11 billion annually, which funds the vast majority of the roughly 17,000 residency positions in the US. The number of positions funded has remained fixed while the population has increased from 269 million to 317 million.

A recent op-ed in the Chicago Sun-Times supports this argument, urging support for several bills in Congress that would increase Medicare funding to support an additional 15,000 residencies.

In 2014, 41.6% of all applicants for residency positions and 4.8% of US medical school seniors were unable to find a residency through the obligatory National Resident Matching Program (other applicants include Americans educated elsewhere, American-educated graduates who were not matched in previous years, and foreigners who pass the stringent requirements of the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates). If the purpose of the system is to complete the education of graduates of American medical schools, who have already survived many rounds of weeding-out, it failed to accomplish this for an estimated 827 of them (up from 528 in 2013). If the purpose is to create more doctors in America, it is squandering the opportunity to do so by admitting less than 60% of fully-schooled doctors seeking to enter the workforce.

Others contend that the bottleneck is intentionally maintained by the medical community to sustain high wages, particularly in higher-paying specialties. As far back as Milton Friedman’s 1962 Capitalism and Freedom, the American Medical Association has been accused of acting as a cartel. Friedman argues that the licensing system for doctors serves only doctors, decreasing quality of care and increasing prices.

This idea was supported by a 2003 report from the National Bureau of Economic Research, in which the author blames the residency review committees (RRCs) for each specialty (which are composed of doctors in the field along with representatives of the AMA and are responsible for approving new residency positions) for creating a monopoly at the expense of medical consumers. The author further claims that residency positions in lucrative specialties like dermatology and surgery would be filled even if the residents were required to pay tuition rather than receive a salary. Others contend that hospitals benefit sufficiently from having residents that the government subsidies are not required, and that the RRCs are the primary barrier to educating more doctors.

These arguments bring into question the source of the shortage, but most agree that the current system is not producing enough physicians to serve the growing needs of the population with current techniques.

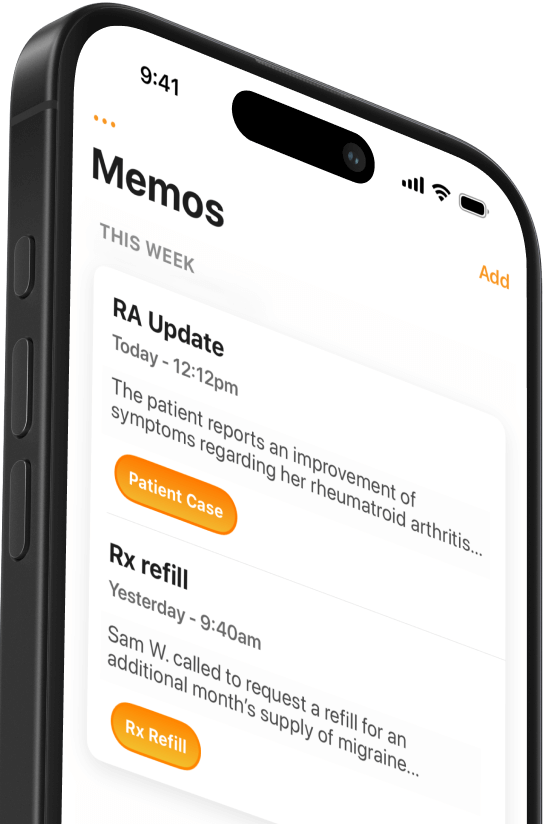

But an op-ed in The New York Times expresses hope that embracing and fully employing our technological advancements, as part of a new, more efficient medical system, is likely to reduce the shortage. He points out that innovation in mHealth, “such as sensors that enable remote monitoring of disease and more timely interventions, can help pre-empt the need for inpatient treatment.” Better communication between patients at home and medical providers can aid in keeping patients healthy and keeping them out of the hospital, and might stave off the doctor shortage at the same time.

Related Articles

We Get Doctors Home on Time.

Contact us

We proudly offer enterprise-ready solutions for large clinical practices and hospitals.

Whether you’re looking for a universal dictation platform or want to improve the documentation efficiency of your workforce, we’re here to help.