Healthcare's Top Medical AI Scribe

Conveyor AI completes over 80% of your EMR notes, simply by listening.

Select Your Solution

Use the industry's best medical dictation or opt for a fully-automated documentation solution—each tailored to your workflow.

Start Dictating Immediately

Conveyor types exactly what you say, even the most complex medical terminology.

Your Notes, Written Instantly

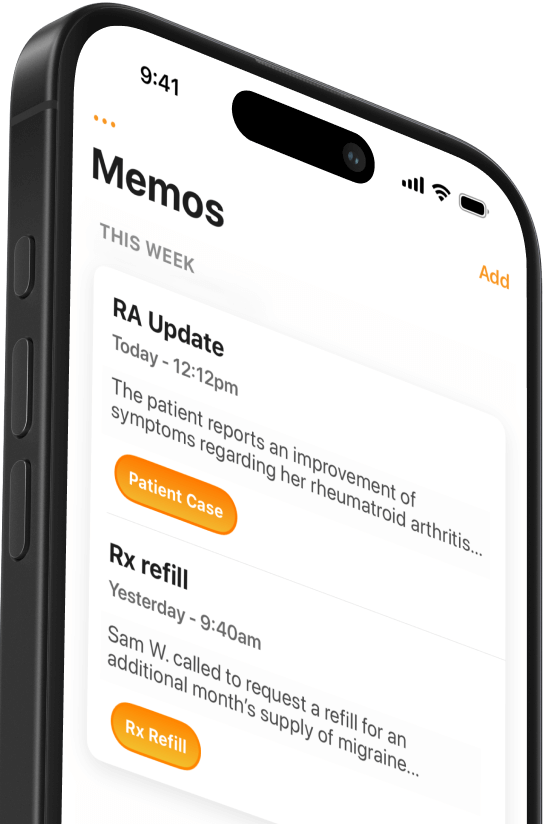

Conveyor AI listens and efficiently writes your customized notes for you.

Free Trials & Simple Pricing

Be confident Conveyor is right for you and your practice. There are no hidden costs or surprise fees.

HIPAA-Compliant & Made for Medicine

Made for busy clinicians, Conveyor exceeds standards specified by HIPAA and HITECH.

Works With any EMR on Mac & Windows

Wherever you place a cursor for typing, you can now dictate instead.

Used and Loved by Thousands of Physicians

Conveyor AI is the premium documentation solution designed by and for medical professionals.

Internal medicine, have been using this app for two weeks now. It is great and on par with Dragon which is what I used before. The medical dictation is very accurate, connection is smooth, lots of options on creating templates and for phrases. Can use on any program and EMR screens. And prices are much more reasonable than dragon. Just signed up for a year contract.

This application is the only dictation that I’ve been able to find [...] that would be comparable to Apple products where you can actually dictate directly into the chart.

MobiusMD is a game-changer for my practice! The intuitive UI/UX makes navigation a breeze, allowing me to focus more on patient care and less on administrative tasks.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there’s no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows.

I was looking for voice dictation that was simple and easy to use and this was it. I already have a number of word templates on my desktop and a system in my office that I could readily type into.

Life Changer -I was a long time, multi year user of a competitor (DAX/nuance). I have been using Mobius for approximately four months and it has been a game changer for me and my practice. I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am a busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

Excellent addition to your documentation - This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings. The biggest change I immediately noticed was how fast I finished charting, general notes, and emails; and I have been significantly less fatigued at the end of my day. I highly recommend it and have deployed it to my medical group.

This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings.

Thank you Mobius I am so happy about this just closed a chart with conveyor. To me: It is such a shame how much faster Conveyor gets a quality note and the how easy It is to transfer the note to EHR compared to Dax. I appreciate Dax but to me Mobius is much better and makes as a provider so less hectic😊 Thanks so much !

Our providers are loving the AI Conveyor and uncovered another feature... creating an automated patient discharge instruction document!

I Absolutely love it, I want to keep it, I let Cayce know and all my colleagues have as well Excellent product!!!

I was blown away by the AI and was like a kid at Christmas.

Oh yay!!! thank you so much! This tech really has been a game changer

Your product really helps me thank you

I have been loving the Conveyor app. Integrating it more every day.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there's no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows. Customer service is also very responsive and can answer questions very quickly. Nice product.

Very helpful product.

I have been using the Mobius app for over a year now. I am a mobile sonographer and I also do home office Tele radiology. I am also a Mac user. My bus has worked very well for me while I am on the road consulting, a real time saver. It is also a great time saver when I am dictating Tele radiology reports. The support team has also been great to work with. I have recommended the app to one of my mobile sonography colleagues and they also really like it.

This company really shines in its customer service. They are easy to get a hold of and amazingly responsive...

I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

Amazing. I have tried several AI programs. As a dermatolofist we have an average of 6 different diagnosis in a visit and the organization and thought processing is near perfect. And the grammar and words make me sound smarter than I am. Worth every penny

Internal medicine, have been using this app for two weeks now. It is great and on par with Dragon which is what I used before. The medical dictation is very accurate, connection is smooth, lots of options on creating templates and for phrases. Can use on any program and EMR screens. And prices are much more reasonable than dragon. Just signed up for a year contract.

This application is the only dictation that I’ve been able to find [...] that would be comparable to Apple products where you can actually dictate directly into the chart.

MobiusMD is a game-changer for my practice! The intuitive UI/UX makes navigation a breeze, allowing me to focus more on patient care and less on administrative tasks.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there’s no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows.

I was looking for voice dictation that was simple and easy to use and this was it. I already have a number of word templates on my desktop and a system in my office that I could readily type into.

Life Changer -I was a long time, multi year user of a competitor (DAX/nuance). I have been using Mobius for approximately four months and it has been a game changer for me and my practice. I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am a busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

Excellent addition to your documentation - This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings. The biggest change I immediately noticed was how fast I finished charting, general notes, and emails; and I have been significantly less fatigued at the end of my day. I highly recommend it and have deployed it to my medical group.

This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings.

Thank you Mobius I am so happy about this just closed a chart with conveyor. To me: It is such a shame how much faster Conveyor gets a quality note and the how easy It is to transfer the note to EHR compared to Dax. I appreciate Dax but to me Mobius is much better and makes as a provider so less hectic😊 Thanks so much !

Our providers are loving the AI Conveyor and uncovered another feature... creating an automated patient discharge instruction document!

I Absolutely love it, I want to keep it, I let Cayce know and all my colleagues have as well Excellent product!!!

I was blown away by the AI and was like a kid at Christmas.

Oh yay!!! thank you so much! This tech really has been a game changer

Your product really helps me thank you

I have been loving the Conveyor app. Integrating it more every day.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there's no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows. Customer service is also very responsive and can answer questions very quickly. Nice product.

Very helpful product.

I have been using the Mobius app for over a year now. I am a mobile sonographer and I also do home office Tele radiology. I am also a Mac user. My bus has worked very well for me while I am on the road consulting, a real time saver. It is also a great time saver when I am dictating Tele radiology reports. The support team has also been great to work with. I have recommended the app to one of my mobile sonography colleagues and they also really like it.

This company really shines in its customer service. They are easy to get a hold of and amazingly responsive...

I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

Amazing. I have tried several AI programs. As a dermatolofist we have an average of 6 different diagnosis in a visit and the organization and thought processing is near perfect. And the grammar and words make me sound smarter than I am. Worth every penny

Internal medicine, have been using this app for two weeks now. It is great and on par with Dragon which is what I used before. The medical dictation is very accurate, connection is smooth, lots of options on creating templates and for phrases. Can use on any program and EMR screens. And prices are much more reasonable than dragon. Just signed up for a year contract.

This application is the only dictation that I’ve been able to find [...] that would be comparable to Apple products where you can actually dictate directly into the chart.

MobiusMD is a game-changer for my practice! The intuitive UI/UX makes navigation a breeze, allowing me to focus more on patient care and less on administrative tasks.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there’s no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows.

I was looking for voice dictation that was simple and easy to use and this was it. I already have a number of word templates on my desktop and a system in my office that I could readily type into.

Life Changer -I was a long time, multi year user of a competitor (DAX/nuance). I have been using Mobius for approximately four months and it has been a game changer for me and my practice. I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am a busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

Excellent addition to your documentation - This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings. The biggest change I immediately noticed was how fast I finished charting, general notes, and emails; and I have been significantly less fatigued at the end of my day. I highly recommend it and have deployed it to my medical group.

This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings.

Thank you Mobius I am so happy about this just closed a chart with conveyor. To me: It is such a shame how much faster Conveyor gets a quality note and the how easy It is to transfer the note to EHR compared to Dax. I appreciate Dax but to me Mobius is much better and makes as a provider so less hectic😊 Thanks so much !

Our providers are loving the AI Conveyor and uncovered another feature... creating an automated patient discharge instruction document!

I Absolutely love it, I want to keep it, I let Cayce know and all my colleagues have as well Excellent product!!!

I was blown away by the AI and was like a kid at Christmas.

Oh yay!!! thank you so much! This tech really has been a game changer

Your product really helps me thank you

I have been loving the Conveyor app. Integrating it more every day.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there's no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows. Customer service is also very responsive and can answer questions very quickly. Nice product.

Very helpful product.

I have been using the Mobius app for over a year now. I am a mobile sonographer and I also do home office Tele radiology. I am also a Mac user. My bus has worked very well for me while I am on the road consulting, a real time saver. It is also a great time saver when I am dictating Tele radiology reports. The support team has also been great to work with. I have recommended the app to one of my mobile sonography colleagues and they also really like it.

This company really shines in its customer service. They are easy to get a hold of and amazingly responsive...

I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

Amazing. I have tried several AI programs. As a dermatolofist we have an average of 6 different diagnosis in a visit and the organization and thought processing is near perfect. And the grammar and words make me sound smarter than I am. Worth every penny

Amazing. I have tried several AI programs. As a dermatologist we have an average of 6 different diagnosis in a visit and the organization and thought processing is near perfect. And the grammar and words make me sound smarter than I am. Worth every penny

Very helpful product.

I have been using the Mobius app for over a year now. I am a mobile sonographer and I also do home office Tele radiology. I am also a Mac user. My bus has worked very well for me while I am on the road consulting, a real time saver. It is also a great time saver when I am dictating Tele radiology reports. The support team has also been great to work with. I have recommended the app to one of my mobile sonography colleagues and they also really like it.

This company really shines in its customer service. They are easy to get a hold of and amazingly responsive...

I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there's no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows. Customer service is also very responsive and can answer questions very quickly. Nice product.

I have been loving the Conveyor app. Integrating it more every day.

Your product really helps me thank you

Internal medicine, have been using this app for two weeks now. It is great and on par with Dragon which is what I used before. The medical dictation is very accurate, connection is smooth, lots of options on creating templates and for phrases. Can use on any program and EMR screens. And prices are much more reasonable than dragon. Just signed up for a year contract.

I was blown away by the AI and was like a kid at Christmas.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there’s no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows.

Life Changer -I was a long time, multi year user of a competitor (DAX/nuance). I have been using Mobius for approximately four months and it has been a game changer for me and my practice. I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am a busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

MobiusMD is a game-changer for my practice! The intuitive UI/UX makes navigation a breeze, allowing me to focus more on patient care and less on administrative tasks.

Excellent addition to your documentation - This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings. The biggest change I immediately noticed was how fast I finished charting, general notes, and emails; and I have been significantly less fatigued at the end of my day. I highly recommend it and have deployed it to my medical group.

This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings.

Thank you Mobius I am so happy about this just closed a chart with conveyor. To me: It is such a shame how much faster Conveyor gets a quality note and the how easy It is to transfer the note to EHR compared to Dax. I appreciate Dax but to me Mobius is much better and makes as a provider so less hectic😊 Thanks so much !

I was looking for voice dictation that was simple and easy to use and this was it. I already have a number of word templates on my desktop and a system in my office that I could readily type into.

Our providers are loving the AI Conveyor and uncovered another feature... creating an automated patient discharge instruction document!

I Absolutely love it, I want to keep it, I let Cayce know and all my colleagues have as well Excellent product!!!

This application is the only dictation that I’ve been able to find [...] that would be comparable to Apple products where you can actually dictate directly into the chart.

Amazing. I have tried several AI programs. As a dermatologist we have an average of 6 different diagnosis in a visit and the organization and thought processing is near perfect. And the grammar and words make me sound smarter than I am. Worth every penny

Very helpful product.

I have been using the Mobius app for over a year now. I am a mobile sonographer and I also do home office Tele radiology. I am also a Mac user. My bus has worked very well for me while I am on the road consulting, a real time saver. It is also a great time saver when I am dictating Tele radiology reports. The support team has also been great to work with. I have recommended the app to one of my mobile sonography colleagues and they also really like it.

This company really shines in its customer service. They are easy to get a hold of and amazingly responsive...

I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there's no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows. Customer service is also very responsive and can answer questions very quickly. Nice product.

I have been loving the Conveyor app. Integrating it more every day.

Your product really helps me thank you

Internal medicine, have been using this app for two weeks now. It is great and on par with Dragon which is what I used before. The medical dictation is very accurate, connection is smooth, lots of options on creating templates and for phrases. Can use on any program and EMR screens. And prices are much more reasonable than dragon. Just signed up for a year contract.

I was blown away by the AI and was like a kid at Christmas.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there’s no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows.

Life Changer -I was a long time, multi year user of a competitor (DAX/nuance). I have been using Mobius for approximately four months and it has been a game changer for me and my practice. I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am a busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

MobiusMD is a game-changer for my practice! The intuitive UI/UX makes navigation a breeze, allowing me to focus more on patient care and less on administrative tasks.

Excellent addition to your documentation - This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings. The biggest change I immediately noticed was how fast I finished charting, general notes, and emails; and I have been significantly less fatigued at the end of my day. I highly recommend it and have deployed it to my medical group.

This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings.

Thank you Mobius I am so happy about this just closed a chart with conveyor. To me: It is such a shame how much faster Conveyor gets a quality note and the how easy It is to transfer the note to EHR compared to Dax. I appreciate Dax but to me Mobius is much better and makes as a provider so less hectic😊 Thanks so much !

I was looking for voice dictation that was simple and easy to use and this was it. I already have a number of word templates on my desktop and a system in my office that I could readily type into.

Our providers are loving the AI Conveyor and uncovered another feature... creating an automated patient discharge instruction document!

I Absolutely love it, I want to keep it, I let Cayce know and all my colleagues have as well Excellent product!!!

This application is the only dictation that I’ve been able to find [...] that would be comparable to Apple products where you can actually dictate directly into the chart.

Amazing. I have tried several AI programs. As a dermatologist we have an average of 6 different diagnosis in a visit and the organization and thought processing is near perfect. And the grammar and words make me sound smarter than I am. Worth every penny

Very helpful product.

I have been using the Mobius app for over a year now. I am a mobile sonographer and I also do home office Tele radiology. I am also a Mac user. My bus has worked very well for me while I am on the road consulting, a real time saver. It is also a great time saver when I am dictating Tele radiology reports. The support team has also been great to work with. I have recommended the app to one of my mobile sonography colleagues and they also really like it.

This company really shines in its customer service. They are easy to get a hold of and amazingly responsive...

I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there's no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows. Customer service is also very responsive and can answer questions very quickly. Nice product.

I have been loving the Conveyor app. Integrating it more every day.

Your product really helps me thank you

Internal medicine, have been using this app for two weeks now. It is great and on par with Dragon which is what I used before. The medical dictation is very accurate, connection is smooth, lots of options on creating templates and for phrases. Can use on any program and EMR screens. And prices are much more reasonable than dragon. Just signed up for a year contract.

I was blown away by the AI and was like a kid at Christmas.

I was looking for a replacement for dragon when it was no longer being supported on a Mac. The dictation system works flawlessly. I like the fact that there’s no hardware necessary and I can use it on any device. I have via Mac or windows.

Life Changer -I was a long time, multi year user of a competitor (DAX/nuance). I have been using Mobius for approximately four months and it has been a game changer for me and my practice. I cannot more strongly recommend this company if you are scribe. I am a busy orthopedic surgeon trying to get through approximately 24 patients in a day.

MobiusMD is a game-changer for my practice! The intuitive UI/UX makes navigation a breeze, allowing me to focus more on patient care and less on administrative tasks.

Excellent addition to your documentation - This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings. The biggest change I immediately noticed was how fast I finished charting, general notes, and emails; and I have been significantly less fatigued at the end of my day. I highly recommend it and have deployed it to my medical group.

This has made an incredible improvement in the speed of my workflow. I primarily do telemedicine, and the interface is excellent as I toggle through my various taskings.

Thank you Mobius I am so happy about this just closed a chart with conveyor. To me: It is such a shame how much faster Conveyor gets a quality note and the how easy It is to transfer the note to EHR compared to Dax. I appreciate Dax but to me Mobius is much better and makes as a provider so less hectic😊 Thanks so much !

I was looking for voice dictation that was simple and easy to use and this was it. I already have a number of word templates on my desktop and a system in my office that I could readily type into.

Our providers are loving the AI Conveyor and uncovered another feature... creating an automated patient discharge instruction document!

I Absolutely love it, I want to keep it, I let Cayce know and all my colleagues have as well Excellent product!!!

This application is the only dictation that I’ve been able to find [...] that would be comparable to Apple products where you can actually dictate directly into the chart.

We Get Doctors Home on Time.

Contact us

We proudly offer enterprise-ready solutions for large clinical practices and hospitals.

Whether you’re looking for a universal dictation platform or want to improve the documentation efficiency of your workforce, we’re here to help.