Medical errors are the third most common cause of death in the United States, according to a study by researchers at John Hopkins University. Data from the CDC now reflects this reality, listing “Accidents (unintentional injuries)” after cancer and heart disease as one of the leading causes of death. Each year, roughly 250,000 people die from preventable medical errors.

As John Hopkins reported in an article about the research, the take home message of this study isn’t that doctors are negligent. Rather, “most errors represent systemic problems” such as poorly coordinated care, fragmented insurance networks and underuse of safety nets.

The good news is that redesigning systems in healthcare can avoid errors and save thousands of lives a year. While the biggest leverage points are in larger institutions, independent medical practices can also play a role. Knowing the principles of mistake proofing can help smaller practices avoid medical errors.

What is mistake proofing?

Mistake proofing is an operational strategy formalized by Japanese manufacturers in the 1960s under the term “poka yoke.” It has since been adopted in a range of industries with the goal of building constraints that prevent errors in a process.

Ideally, mistake proofing ensures that the proper conditions exist to prevent errors before they happen. If this isn’t possible, the goal is to eliminate mistakes in the process as early as possible. In healthcare, mistake proofing is one effective way to avoid medical errors.

Use mistake proofing to avoid medical errors

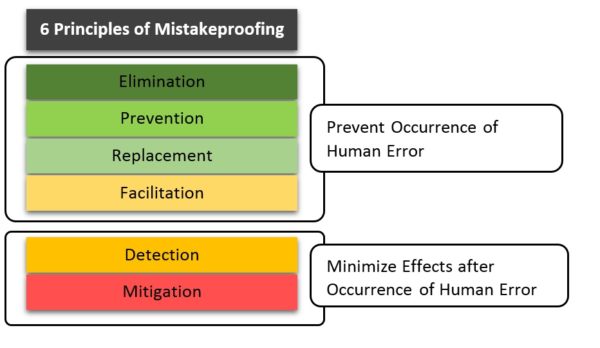

The following six principles – derived from poka yoke – can help identify ways to avoid preventable errors in your medical practice.

1. Elimination

The first step is to analyze a process and removing any steps susceptible to human error. The hardest part of elimination is often defining the steps that make up each process, and it can be helpful to have the perspective of an outsider or consultant.

Example: A common problem in many medical offices is handling requests for medication refills. This process has many steps:

- patient leaves message with receptionist

- receptionist pulls charge, gives to nurse

- nurse reviews charge and calls the patient back for additional information

- nurse conveys chart to provider

- provider responds to nurse with medication order

- nurse calls prescription to pharmacy

A easy way to simplify and reduce possible errors in this process would be to remove the receptionist from the loop, so that calls for refill are initially directed to the nurse.

2. Replacement

Replacement often looks a lot like elimination. This is especially true as it becomes possible for health IT to replace operations prone to mistakes.

Example: Collecting vital signs is a process with several steps susceptible to human error. Typically an assistant or technician is responsible for collecting vitals, recording them on paper, and later entering the information into an electronic medical record (EMR). New devices and software can now automatically send vitals from digital monitors to EMRs, replacing the steps in this process that are prone to transcription errors.

3. Facilitation

Facilitation is the process of making operations easier to compete correctly. This can involve:

- simplifying by reducing the number of alternatives or variations in a repeated process

- differentiating more clearly between similar actions or times

- adjusting some aspect of a process to eliminate the potential error

Example: Patients with asthma are sometimes prescribed three different inhaled medications, which can have similar names but different dosing regimen and intended use. Color coding inhalers has been a successful way to help prevent errors so patients use the correct medication when symptoms develop.

http://45.33.12.216/blog/2019/06/5-best-practices-to-boost-emr-productivity/

4. Detection

Detection means catching mistakes and correcting them as soon as possible. Late detection leads to greater negative impact and corrective actions, so mistake proofing creates multiple checkpoints that catch mistakes as close to the source as possible.

Example: In surgery, the anesthetist carefully monitors vital signs minute by minute to catch problems early. This can initiate rapid investigation of the source of the problem (e.g. infected bleeding, incorrect clamp placement) and correction.

5. Mitigation

Mitigation accepts the fact that errors will occur and aims to reduce their impact. While every effort should be made to detect mistakes before they reach the patient, mitigation also focuses on creating ‘safe’ failures at operational points most susceptible to error.

Example: When a physician receives an unusual lab result it is often sent back to be run a second time on the same specimen. This process of repeating and verifying the results is a fairly easy, low cost way of making sure errors are caught and corrected before they reach the patient.

6. Patient involvement

Patient involvement gets patients and families engaged in care to ensure there are additional eyes on the process. Perhaps more importantly, patients and families are the people most invested in a positive outcome, and they can be a good source of information.

Example: Mistake proofing in this context can involve setting patients’ and families’ expectations for what should happen, and encouraging them to ask questions at any point in the treatment plan. Organizations like the UCLA Medical Center have developed explicit patient involvement strategies through their Partnership in Safety Program.

Mistake proofing in medicine

While the first three principles – elimination, replacement, and facilitation – are ways to prevent mistakes from occurring, detection and mitigation aim to minimize the effects of errors once they occur. Patient involvement is especially important because it brings in elements of both prevention and minimization.

Applying these principles to a range of processes can help you organize your practice to reduce mistakes, lower costs and improve patient outcomes.

http://45.33.12.216/blog/2019/08/top-5-tools-to-reduce-data-entry-errors-in-ehrs/